A discussion of arts accessibility in theatre

Following the release of a distressing story in the Sydney Morning Herald (read here for a full run-down of facts and statements from both parties) last month claiming that a young girl with a disability and her mother were asked to leave a performance of Matilda at the Sydney Lyric Theatre, I’m pretty annoyed that any professional in our industry would place the experience of a fully-abled audience member above that of a differently-abled person.

Following a reading of the official incident report, Kearns also stated that Eliza was seen to be “expressing herself pretty loudly with a lot of movement”, and that those seated around her “were indicating that they wanted to enjoy the performance”. Hirst maintains that her daughter was not being disruptive, merely responding in her own way to the stimulating stage environment, so it sounds to me as though Eliza was also indicating that she wanted to enjoy the performance.

The question on my mind is this: why were the needs of other audience members placed above that of Eliza and her mother by the days’ theatre staff? If a young woman in accessible seating is causing a minor disruption to the rest of the audience, what about her theatrical experience invalidates the experience of a fully-abled person? What right do we have to deny a person an experience in the theatre if they only slightly change our own? I have personally sat in an auditorium with audiences who allow their phones to ring out multiple times, with audience members who have sung loudly along with the score, who show up late for performances and subsequently force entire rows of people to stand up to allow access to their seats, and with people who simply can’t leave their reviews until after the show so instead make loud comments to their friends the whole way through. Why is this detracting behaviour tolerated, and why is the reaction to it nowhere as disdainful as that given to the vocal or physical reactions of a differently-abled person?

Late last year, a social media post from Kelvin Moon Loh (an understudy and ensemble member in Broadway’s The King and I) regarding autism in the theatre went viral. According to Moon Loh, an autistic child became distressed during a scene of physical violence within the show and “yelped” in terror. He characterises the reaction of the audience as “plain wrong”, after hearing whispers from them along the lines of, “why would you bring a child like that to the theatre?” He also states that the week earlier, a non-autistic child had a similar reaction, and she and her parents were not berated by other audience members for simply reacting to the scene in front of them.

There is clearly a cultural double standard at work both in Australia and overseas. When ‘relaxed performances’ (which I will further explain later) have to be purposefully created so that parents and carers of differently-abled children can sit in a theatre house with a group of people who will keep their nasty comments and side-eyes to themselves, I have to wonder where the compassion and understanding of our general audiences has gone.

Theatre attendance is seen by many as the ultimate form of escapism, and a wonderful way to lose yourself for a few hours, but audiences these days must remember that viewing a piece of stage art is not a solitary experience. Life will continue around you in the dark of the theatre, and your experience is no more important than that of the person sitting next to you. People react to the world presented to them on the stage in many ways, and the broad scope of these reactions only becomes wider when some audience members are not neurotypical. Life informs the reactions we have to art, and anyone who attends the theatre has the right to laugh, cry, applaud, exclaim and generally react in any way their body and brain tells them to. If you attend a theatre performance and leave the venue angry because the differently-abled person sitting near you responded to the presented material in a way foreign to your own reaction, then a better entertainment option for you might be a Netflix session in the comfort of your own home.

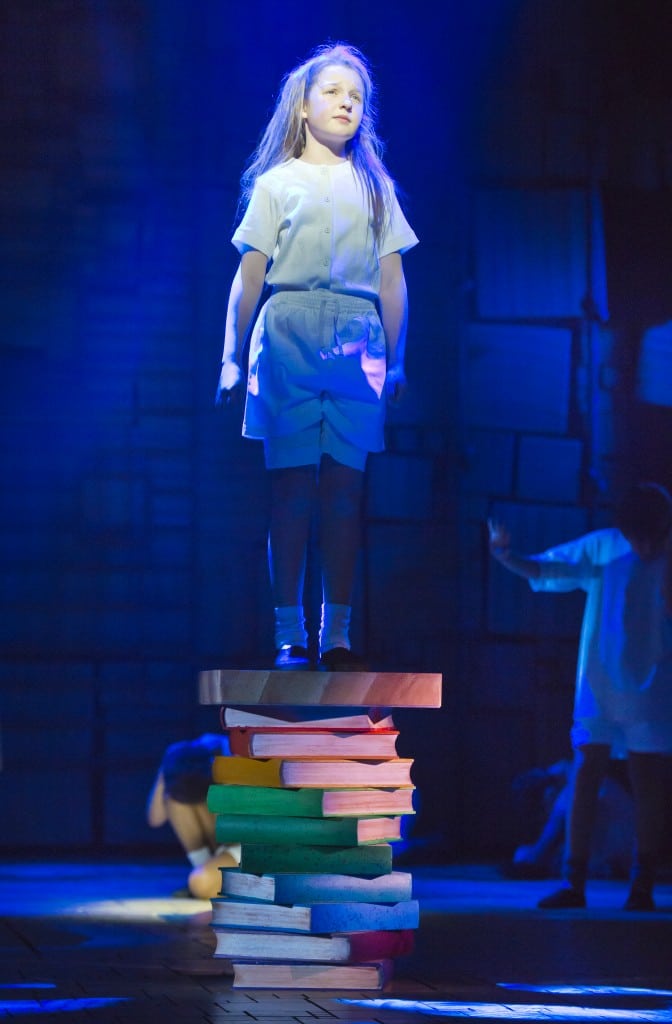

The Hirst family were clearly victims of discrimination in the Australian theatre industry this weekend, and every aspect of their treatment leaves a lot to be desired. According to Hirst, the floor manager told her that there were “more appropriate shows” for her daughter to attend. Putting the issue of policing audience content aside, this comment, to me, is puzzling. Matilda is a family-friendly show, and the themes it explores seem like a great choice for the Hirst family.

Although never explicitly stated by the authors of the various incarnations of Matilda, there are people out there (I am one of them) who have always believed Matilda Wormwood and her abilities to be a physical, magical manifestation of symptoms and behaviours exhibited by those on the autism spectrum. If you listen to Matilda’s gorgeous solo, ‘Quiet’, with this hypothesis in mind, you can clearly draw a parallel between Matilda’s words and the difficulty many autistic people have with sensory processing. A show that teaches viewers to admire all manner of children as their own self-contained miracle, no matter their differences, is a show that should throw its arms wide open to differently-abled audiences. Which brings me to the second reason the “more appropriate shows” comment left me angrier than the dreaded Trunch discovering Bruce Bogtrotter had eaten her precious cake…

The original London production of Matilda the Musical was one of the first to trial the process of what we today call “relaxed performances”, where theatre venues and content are modified to suit an expansive spectrum of audience members’ special needs. To see a differently-abled audience member removed from her seat for the comfort of neurotypical patrons in Australia while the London production of the same show offers annual relaxed performances (as well as a wide range of other accessible performances) is disappointing and embarrassing behaviour from our industry professionals.

Differently-abled people have a hard enough time accessing the things that are so naturally afforded to most of the theatre going population by their able bodies, and theatre as an industry and as an art form needs to pick up its game entirely to create a safe and accessible place for people of all abilities. Patting small groups and initiatives on the back for their forward-thinking attitude to different abilities in the theatre is all well and good, but an accessible world should not have to be begged for by those that need it – it should simply be a given.

Setting aside a few seats in a theatre venue does not an accessible venue make. At a bare minimum, staff need to be trained to facilitate audience members with different and varying needs, and the comfort of fully-abled audience members should not be placed over the rights of a differently-abled audience member to simply see a show. Graeme Kearns has offered for the Hirst family to return to see a different show as guests of the theatre, and he states in the Sydney Morning Herald article that removing Eliza and her mother from the audience that day was the lesser of two evils, as the alternative would result in patron complaints and would find him sorting through “a hundred letters […] from people wanting their money back.” This may have been the case, but accessible theatre for differently-abled people is not optional in 2016. It should be an industry-wide moral imperative for any theatre maker or venue.

Over the coming months, AussieTheatre hopes to bring you interviews with theatre makers and audiences of differing abilities. If you have ideas on how to make Australian theatre more accessible or specialise in offering theatrical experiences to a certain group of people, whether they be deaf audiences, blind audiences, those audience members on the autism spectrum or similar, we would love to hear from you.

Contact: [email protected]

Thanks for your article Maddi. You’ve really distilled the issue well.