State Opera of SA: Satyagraha

Satyagraha appropriately and magnificently concludes the first cycle of State Opera of South Australia’s Portrait Trilogy of operas by Philip Glass, soaking the soul and leaving you blessed with something special.

Meaning “truth force” from Sanskrit, satyagraha is a term adopted by Mahatma Ghandi to describe his philosophy of non-violent resistance. The opera’s three acts depict episodes in his life with a breathtaking performance by Adam Goodburn who seemingly channels Gandhi’s spirit and elevates him to the status of a god. “Mahatma” is, after all, an honorific title meaning “venerable” and “high-souled”.

Satyagraha is, chronologically, the second opera of the trilogy, first performed by the Netherlands Opera in 1980. As the last performed in this world-first, three-cycle trilogy, however, it bookends suitably with the first performed, Akhnaten, thereby centralising the longer and plotless Einstein on the beach. Of the three operas, it depicts its central character with the greatest clarity.

Considering the trilogy, for me, it is the most successfully integrated of the three from director and choreographer Leigh Warren, and State Opera of South Australia artistic director, CEO and conductor Timothy Sexton. The result is a wondrous balance of dance, music and voice, which, by the opera’s end, might make you feel as if you’ve travelled on your own journey to enlightenment.

This time, the action is beautifully grafted to Mary Moore’s modest set design. Most of the action unfolds on a flight of steps spanning the forestage, and a large circular cut-out at the rear is used effectively for both a backdrop and entry/exit points. Only occasionally do a few simple scenic drops and props appear to provide a sense of place. Even the auditorium is used, for a surprise distribution of political leaflets via an “airdrop” to the audience. The visual offering is aided by Moore’s costumes of English suits, Indian robes and saris, which tint the stage in a soft exoticism, and Geoff Cobham’s varied and dramatic lightning. Nothing seemed amiss.

Conceptually, the power of Glass’s work lies in its ability to express opera’s essence in the most reductive, resonating and magical way. Satyagraha is sung in Sanskrit, to a libretto (adapted from the ancient scripture the Bhagavad-Gita) by Glass and Constance DeJong.

Although a translation is sometimes provided, it’s unnecessary, as the actual action on stage bears no relation to the text. Glass didn’t intend it to be understood, instead, wanting the action on stage to speak for itself. Neither does the souvenir program provide any details about each of the acts, named after a historical figure relevant to Gandhi (Leo Tolstoy, Mahabharata Tagore and Martin Luther King). Furthermore, it isn’t exactly clear who’s who in the extended cast of soloists but after a while, it didn’t matter. Nonetheless, the gentle transition from scene to scene and a cast of superlative strength give a spirit to the performance that sanctifies Gandhi in the process.

Instructing us in the way of peace, Goodburn is Ghandi incarnate. From the English-suited lawyer to the Indian loincloth-dressed leader, Goodburn cuts a charismatic figure. The vocal demands of the role are met with equal conviction. Here, Goodburn navigates the long, stretched chant-like forms and the abrupt changes in pitch with dexterity and poise.

Deborah Caddy (Miss Schlessen), Naomi Hede (Mrs Naidoo), Cherie Boogaart (Kasturbai), Andrew Turner (Mr Kallenbach), Jeremy Tatchell (Parsi Rustomji), Deborah Johnson (Mrs Alexander) and Mark Oates (Arjuna) fill the other principal roles with assuredness, shaping a vocal concoction of beauty and unity.

They are complimented by a tightly controlled and superbly voiced State Opera Chorus, and once again the Leigh Warren Dancers stealthily weave their charm throughout with ritual force. But holding it all together is Timothy Sexton’s expert hand in conducting the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra, allowing the “Glass drug” to work its effect slowly and hypnotically. The entire artistic and creative team deserve praise not only for this production, but also the sentiment and work in undertaking the entire trilogy.

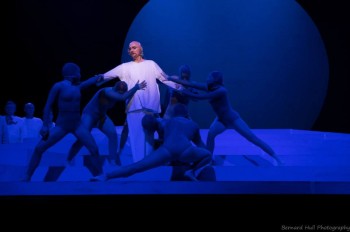

In the final scene, Gandhi sits before us in a halo of soft blue, bare-chested, at peace and radiating sacrosanct energy. A warm, comforting ocean-blue washes the stage and dancers creep across the stairs while the music ebbs and flows at length, simply and soulfully, sweeping you into its trance. Then the performance ends and applause breaks the peace. An abrupt return to the world outside seems wrong, a world where searching for peace is too often made in war-making ways. It shows how little we have learnt about it.

Post Script

For me, the idea of a world premiere presentation of Glasss’ Portrait Trilogy in a three-cycle event conjures a sense of occasion, something that seemed lacking at the opening night of Akhnaten. It didn’t seem to improve for the following two operas, Einstein on the beach and Satyagraha either. Instead, I was taken back to my first memories of hearing Philip Glass’ music in the 1982 cult movie directed by Godfrey Reggio, Koyaanisqatsi, which I saw screened at the grungy, marijuana-scented, but now demolished Valhalla Cinema in Melbourne.

Her Majesty’s Theatre, as dowdy as it is (though clean of air), wasn’t injected with the trimmings and atmosphere of occasion. The theatre’s almost 1000-seat capacity couldn’t be filled on any one of the performances in the first cycle and yet still I wondered why the trilogy couldn’t have been staged at the larger Festival Theatre. I was hoping at least to see the “Sold Out” sign on display.

I thought Glass’s appeal spanned many more generations as evidenced in the enthralled audience at several performances of Einstein on the beach at Melbourne’s State Theatre last year. When these great modern works from the mid 20th century can attract a new and younger audience, locally and beyond, it was disappointing to see an audience average age of around 55-60 years of age in Adelaide.

I also wondered if Adelaide even knew about it. I learnt about the trilogy via an independent search of the State Opera of South Australia website. Arriving in Adelaide, I saw no banners, nothing on the streets, nothing to inform the public as to the significance of this event, the biggest undertaking by State Opera of South Australia since the huge success of the Adelaide Ring Cycle. And when opera companies need to engage with their audiences more than ever through social media, it bemuses me to see the last entry on twitter@StateOperaofSA dated 3 May 2014 referring to a production of La Traviata. Perhaps some things need to change, starting not on the stage but in the office.