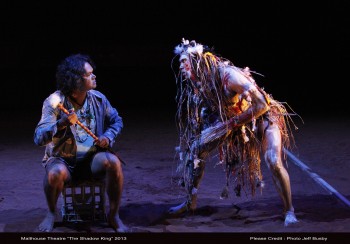

Kamahi Djordan King; the Fool in King Lear

Photo: Jeff Busby

Shakespeare’s King Lear would be incomplete without the Fool. He is one of the most iconic characters, serving to provide comic relief, insight and knowledge in a world consumed by madness and greed. Dione Joseph was able to catch up with Kamahi Djordan King before the opening of The Shadow King.

The Malthouse’s Indigenous adaptation of this classic, The Shadow King, retains the essence of Shakespeare’s vision, but presents it within context of an Indigenous story and landscape specific to the people from the Katherine region in the Northern territory.

Kamahi Djordan King originally wanted to play Edmund, but the role didn’t eventuate.

“They didn’t think I was suitable for Edgar so I let it go,” Kings explains, ‘But then it became apparent that people needed to speak Kriol in this particular production and I happened to come along and became the dialogue and dialect coach.”

This was an important role because Kriol (note the different spelling to Creole) is a registered Aboriginal language and evolved out of a necessity for different tribes to communicate with others, particularly those that lived along the fringes. There are 27 language groups in the Katherine region; four of the major ones are Jawoyn, Wardaman, Duggaman and Mialli.

“It [Kriol] also served as a means to communicate with white folks,” King adds, “Today there are many different Kriols and this story really needs language to locate it.”

But that’s only half the story. After working with the director Michael Kantor and the other cast members to incorporate Kriol into the script another development came to his attention.

“Uncle Jack Charles was originally supposed to play the Fool, but he pulled out. So they were one cast member short and they offered the role to me.”

And now it seems obvious that there was a reason neither Edmund nor Edgar was meant to be. King, as he says with a smile, “was meant to play the fool.”

Photo: Jeff Busby

But for those who are expecting merely a regurgitation of a Shakespearean classic with an Indigenous twist, prepare to be disappointed. The Shadow King is set in an Australian context heavily imbued with the affects of mining, the intervention and land rights, as well as the often taboo topic of lateral violence.

“This play resonates with us because King Lear in our Shadow King production has been offered a lot of money for his land and he’s divvying it up between his three daughters.”

Similar to the original script, it is only the youngest daughter Cordelia who can truly comprehend the magnitude of his actions and her words, “you can’t give me what you don’t own”, reverberate throughout the play.

Shakespearean adaptations are important argues King because, especially in the case of this tragedy, they have “enabled us to look at some of the hard truths in the Aboriginal community, and the fact we’re not afraid to go there allows us to expose an issue we don’t want to touch upon.”

“The fact is that we are paying for the past mistakes; its been over 200 years and that’s five generations. That’s not very long and certain messages have become ingrained in our community: ‘white people hate us, white people will kill you, white people will steal our land.’ … Whatever white folks may think of us, crimes have been committed and its really important to think about these questions: Why do you dislike black fellas so much and, more importantly, why do you have that attitude?”

It is questions such as these that King hopes will be raised during the show. But this isn’t merely a case of Black Australia educating White Australia; the production is also an opportunity for all Indigenous Australians to engage with the issues and concerns that are rife amongst their communities; amongst different groups, clans and families.

“Lear is the Kriol speaker and he’s the one divvying up the lands … Gloucester (in this production played by a woman) is laying claim, and her son has become greedy. This is really about exploring the relationships between the black and the half-caste Aboriginal peoples in Australia,” adds King.

There are textured layers of meaning, symbol, and story interwoven in this production and audiences would do well to remember that while the substance matters, it is equally important to recognize the motivations behind the creation of the characters and the performance.

As King’s character cryptically remarks to his friend: ‘You’re Lear’s shadow you’re nothing but the shadow of a king.’

This is potentially a ground-breaking production and the beginning of a real shift in how Indigenous Australian stories are narrated, shared and engaged with within the wider discourse.