Knives In Hens

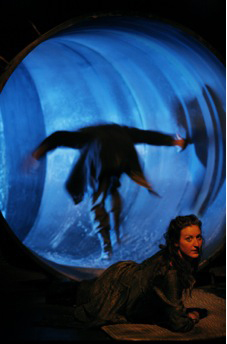

Anna Cordingley’s design strikes before a word is spoken, as she continues to prove her stunning visual aesthetic. We are at the end of huge drain in a world coloured by rust and moss and mud. The circles and water give lighting genius Paul Jackson a canvas that rarely disappoints our eyes – but this beautiful, beautiful design works against the text. I loved how Cordingley’s recent design for Happy Days created an incongruous gap between the text and the design, but here its dissonance is confusing and frustrating.

The huge concrete pipe with the rural-looking costumes and straightforward language of the text immediately establishes a post-now, post-apocalyptic world, as it’s a society that has created giant drains big enough for an industrial city and probably destroyed itself. Suggesting an unknown future, as an audience who know how to read stage language, we search for clues about this world – that aren’t there. In the program, Cordingley says, “The opportunities in the drain pipe offered up for Paul’s lighting and Geordie’s (Brookman – director) physical blocking were instantly compelling.” Which they are, but how does this help to tell the story and share this text?

Harrower’s text is full of metaphors and his magnificent words summon vivid visions of a rural landscape and its struggling people. As productions all over the world have proven, the dense text never restricts the creators in their interpretation, but nothing else in this production is congruous with the giant drain, so the text and the stage worlds never become one.

For all the wonderful things about Knives in Hens, it is a confusing experience. Kate Box, Robert Menzies and Dan Spielman’s performances are individually perfect, but they don’t acknowledge the world they are living in, be it moving through the water the same as they move on solid ground, letting us believe that they can see a village at the other end of the pipe or creating a relationship subtext between the characters.

This could be because Brookman’s direction is felt too much on the stage, from ‘compelling’ blocking that doesn’t always sit with the text to performance levels that restrict the performers. They start so intensely that importance becomes meaningless because they have nowhere to go. There’s a constant tension and we feel and hear a lot of powerful emotion, but it lacks light and shade, and is so relentless that there isn’t enough room for the text to speak.

This production feels like it is trying so hard to bring an originality and a theatrical intelligence to the script, that it forgets to trust the script and forgets to tell the story to the audience. As it runs, it may forget about trying to be so clever and relax enough to let the story free. And, if they can make that drain a vital part of the telling, it may still be seen as one of the best designs of the year.