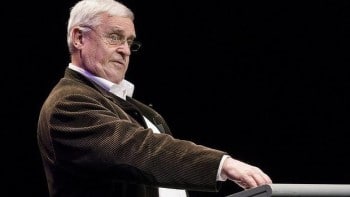

Once Were Leaders: An Evening With Max Gillies

Once Were Leaders looks back in time, but simultaneously compares the past with the present. In the past, it suggests, there were leaders, whereas now … well, not so much.

Drawing from three decades of satirical performance, Max Gillies presents impersonations across the political spectrum: Robert Menzies, Amanda Vanstone, Graham Richardson, Queen Elizabeth, and many more. The sketches originally appeared on stage and television, especially in ABC’s The Gillies Report and The Gillies Republic.

In this stripped-back show, Gillies performs without props, makeup or costume, conjuring his subjects largely through his uncanny vocal abilities. Their monstrous egos loom large, as do wild and disordered ways of thinking. A small number of well-chosen video clips—Robert Menzies’ valentine to young Queen Elizabeth; Bob Hawke attacking journalist Richard Carleton—complement the live performances.

Gillies pays tribute to collaborators who made his performances possible. This is particularly the case in the second half, when he chats informally, providing a fascinating insight into the creative processes behind his television shows. He talks, for example, of his long collaborations with writers of the calibre of Don Watson (later Paul Keating’s speechwriter), cartoonist Patrick Cook with his “icepick-sharp wit”, and a very young Guy Rundle—today Crikey’s writer-at-large.

Gillies also reveals his makeup artists’ magic. But of course, as good as they were, building his impersonations required much more than stuck-on eyebrows. He describes searching for gestures that “get to the essence of what this person was”. Gillies demonstrates Hawke’s “open” gestures, “inclusive, drawing people in to him”, Tony Abbott’s repetitive, mechanical movements, and Kevin Rudd’s “baroque hand ballet”.

Looking back as it does, the show assumes the audience knows their history. The characters are identified only by name—which is fine if you know who Russ Hinze was and why it was funny to depict him as a grotesque beanbag man. And since the point of satire depends on knowing context, the sting evaporates.

In its place though, Gillies’ emotional connections to his subjects seep through. His parodies are absurd rather than cruel. For instance, his intuition that Malcolm Fraser was shy became the key to depicting Fraser’s seeming arrogance. And it is no surprise when Gillies describes his relationship with Bob Hawke as “prickly”; his depiction of Hawke is the least forgiving of all.

In spite of his enormous talent and long stage experience, Gillies seems uncomfortable during the first segment. So many words, so many characters! Perhaps this burden—or perhaps simply the reflective process—introduces the show’s pervasive melancholy. That mood is perfectly reflected in the final sketch. Gillies presents John Howard as dressing-gown-clad “Sandy Stone”, a Barry Humphries character developed long ago. Gillies thus pays tribute to Humphries, whom he calls one of Australia’s greatest satirists.

The Man of Many Faces confesses to confusion about “real and fake politicians”, mired in the mess of images that is politics today. Satire, he suggests, can’t bite if it hasn’t got anything into which to sink its teeth.

And that definitely provokes melancholy.