Review: Unholy Ghosts – Griffin

What happens to us when our immediate family dies? Are the ties that bind us to the earth irrevocably cut? Do we float anchorless, aimless, without that recognition of blood? Can we still be ourselves if we don’t have a family left to remind us who we are and where we came from?

Unholy Ghosts, Campion Decent’s unwinding conversational narrative of a play, looks at exactly this question. Faced with the task of looking after divorced parents who are both dying, our protagonist – a writer and man of the theatre – is, understandably, worried about his place in the world. The terror of being alone, for him, is sharper than usual, because he wasn’t always an only child; he used to have a companion in navigating life in his sister, but she died twelve years ago. “You can’t meet her,” he tells us, as he begins his story. Her death is a wound the family is very much still trying to heal.

For a play about death, Unholy Ghosts is frequently, genuinely funny. With a dying mother who is a faded star of “stage and radio”, there are plenty of “darlings” and various dramatics that can only, even within the throes of tragedy, be ridiculous; add to that a dying realist salesman father possessed of deep pragmatism, resignation and impatience, and the jokes evolve quickly and naturally out of dialogue. In this way the play manages to feel honest and certainly relatable; the human creases of personality that infiltrate the impossibly sad ritual of dying and family loss mean that laughs are still going to happen, and possibly at the worst possible moments. It’s how we keep living.

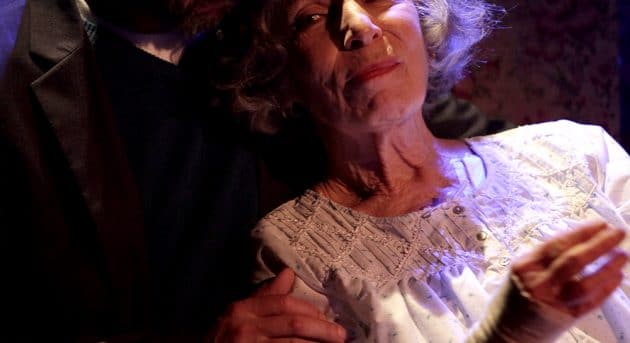

As the mother who wears lipstick even for the priest who is coming to administer her last rites Anna Volska is a hoot, a gand dame with long limbs and a beautiful, likable habit of reciting Shakespeare — everyone loved her Ophelia. Robert Alexander as the gruff father is delightfully cantankerous, and for carrying the entire play, for talking to us and his parents and for feeling the fresh pain of death night upon night James Lugton is excellent, this likable everyman.

There is a compassionate lens over Decent’s play, especially in the steady, sensitive directorial hands of Kim Hardwick. Late in the piece when his mother’s condition has deteriorated, the burdened son addresses us (he constantly addresses us, that is the play’s narrative function) and explains how at some point you start to love the disintegrating skin and seeping wounds and mess and horror of bodies dying, because underneath that mess is your mother, and you love her, and this is the most vulnerable she has ever, and will ever be with you. It is elegiac and tender and behind me, someone broke into fresh sobs.

The son has a more contentious relationship with his father and it’s with him that the play finds itself with another kind of catharsis — the act of finally holding a disappointing parent to task for all the ways he has let you down. Standing there with a bent, exhausted old man who is hardly the figure you used to fear, and finally asking the question a lot of people want to ask their parents: do you realise how much the things you did have affected me and my life? It’s a collective exhale of breath in the audience, a rush of release, a human moment.

In these ways, with these parallel experiences of familial loss, Unholy Ghosts becomes wider-reaching with its relatability; there’s a thread everyone can follow. And certainly it is striking a chord with audiences — some who sniffled and discreetly dabbed at their eyes, and others who didn’t hide their sobs or gasping attempts for breath between tears. When a play touches an audience it’s doing something right.

The thing that lets down this lovely, lived-in, worn and warm story of family and death and life is the ending. Within the last two minutes a peace is found and it comes too soon to feel earned; bubbles cascade onto the stage and he stands underneath them, arms outstretched; he is still connected to the world through his partner, his partner’s family, his children. This is a truth and universal one, but it isn’t satisfying or enjoyable — not when the preceding 85 minutes are an exploration of one idea, and the final couple introduce a new one that could, perhaps have should, have been tighter woven into the earlier play. The uplift comes too easily. Maybe it’s that as an audience we aren’t given time to mourn the parents, who we have just met and begun to love.

Still, it touches something in you, this play — it touches our fears of being alone, of losing our partners in crime that are our siblings, our terror at losing the parents we don’t need to parent us anymore but may still need to understand ourselves. And for its honesty and sense of confessional it is commendable.