The Prince

The Prince is a one-act play superbly written and directed by Rachel Hogan, with its two actors – Peter Fock as Machiavelli and Nicola Tydale-Biscoe as Marietta – giving transformative performances. It offers insight into what it means to be human in a complex political world as well as the political dangers of being too insightful. The stunning, thought-provoking text compelled the audience throughout.

The Prince presents us with Machiavelli in political exile, in a country house overlooking Florence. While writing and having imaginary conversations with leaders and advisors in history, he tries to make sense of his life as a political advisor. The contrast with his domestic life and the concerns of his wife Marietta for his well-being, give us great insight into both the man and also the philosophical questions underpinning political leadership.

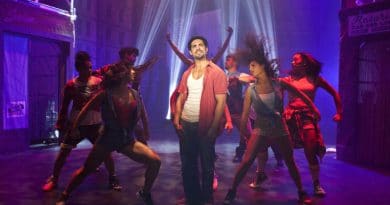

The paired atmospheric setting of a dining room with hand-thrown ceramic pitchers and plates with wine and food laid out, and Machiavelli’s study with desk, books and writing materials, feels intimate. The audience are drawn into Machiavelli’s mind as he writes The Prince. The detailed costumes allow us to enter the familial but defined world of Florence in the mid-1520s. The brief dialogues accent the Italian vernacular in which The Prince was written.

The philosophical questions posed look at humanity and the common-place activities of lying and cheating, and how this compares to the behaviour of political leaders. Hogan presents Machiavelli as he poses these questions to himself about the meaning of persuasion, compassion, virtue, greatness and fear, and what is humane. What is persuasion – that is not begging? How is poignant compassion different from the compassion of princes? How do we understand the mystery of uncommon people and their extreme behaviour? What is virtue versus greatness? How can you compare any other fear to the fear of being plummeted from power? What is benevolence without power?

Machiavelli introduces these philosophical questions to himself and to political leaders and advisors long past: Dante, Caesar, Hannibal, Mark Antony and the princes of Florence. He posits a vision of heaven where the ordinary men and women –adulterers, thieves and betrayers, cowards and fools – are forgiven. This is in contrast to the hell occupied by princes and advisors who are condemned to endlessly question each other about their political insight, about how life is not equal, despite their having knowingly lived life to the full yet, all of them were betrayed and betraying, all of which is presented as the same scenario as Satan is to God.

How all these human characteristics are represented in Machiavelli the man is raised in the monologues and short duologues driven by his wife Marietta. We learn about Machiavelli’s travels throughout Italy, his presents for his children, his delight in talking, his own art of persuasion, his compassion for beggars, how his opinions mattered, his confidence, his trickery, his career path, his adultery, his benevolence and his absence from family life. The underpinning thread throughout is the political pain and suffering inflicted on both his mind through political exile and also his body, from having been sent to prison and briefly tortured, which he accepts as part of the political process – whereas she questions his sanity. This is confronting for Marietta as it is for the audience, although we have the benefit of hindsight and the play itself to value his insight.

This review was submitted to AussieTheatre.com by Kathryn Wells.